BIOMEDICA

An Open Biomedical Image-Caption Archive with Vision-Language Models Derived from Scientific Literature

CVPR 2025

Dataset access

Access the data via HF Datasets 🤗

Contact us

Contact us with questions and suggestions!

Colab Tutorial

Learn how to use our dataset in colab!

Dataset Statistics

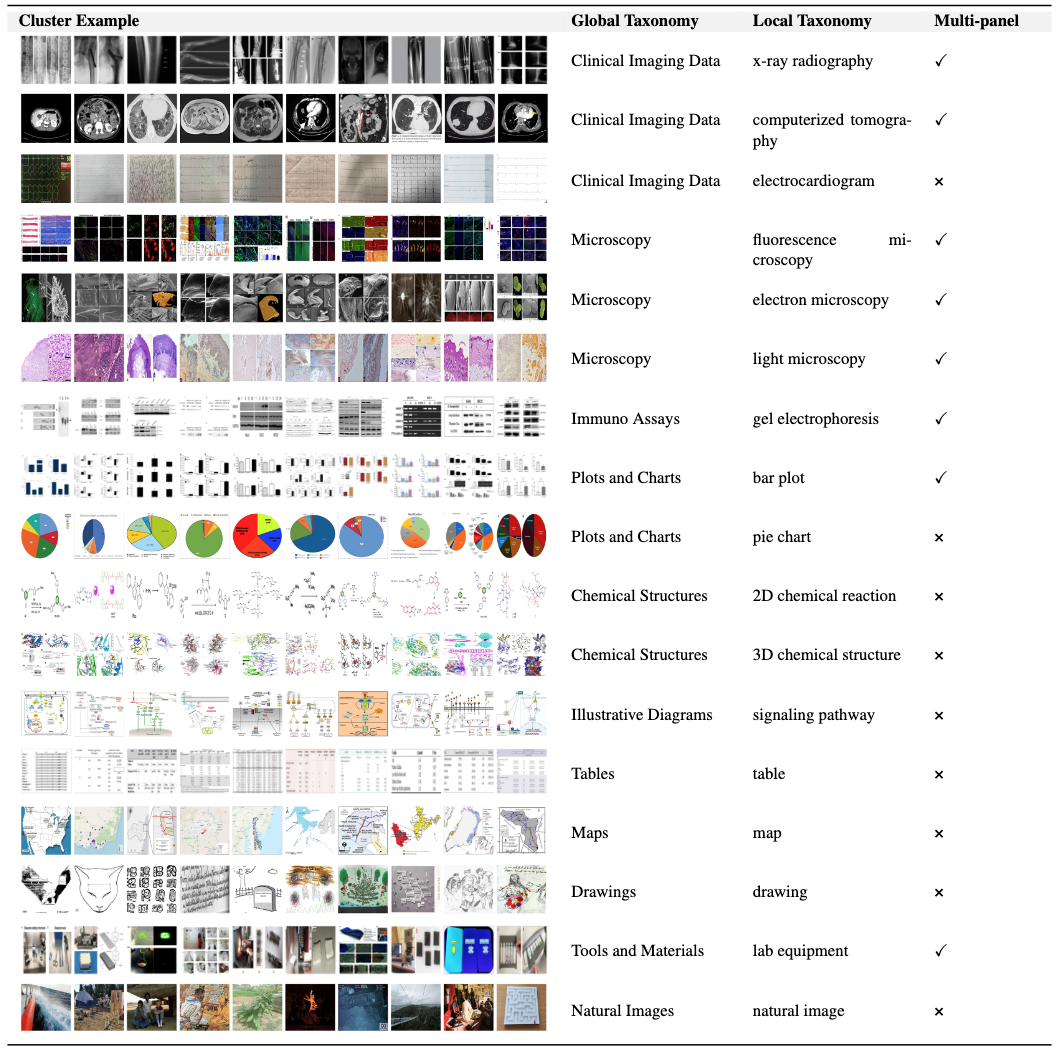

Figure 3: Taxonomy of clusters with example images. Images resized to a uniform width of 10cm and height of 1cm. Column widths adjusted to fit the page.

Figure 3: Taxonomy of clusters with example images. Images resized to a uniform width of 10cm and height of 1cm. Column widths adjusted to fit the page.Continual Pretraining Experiments

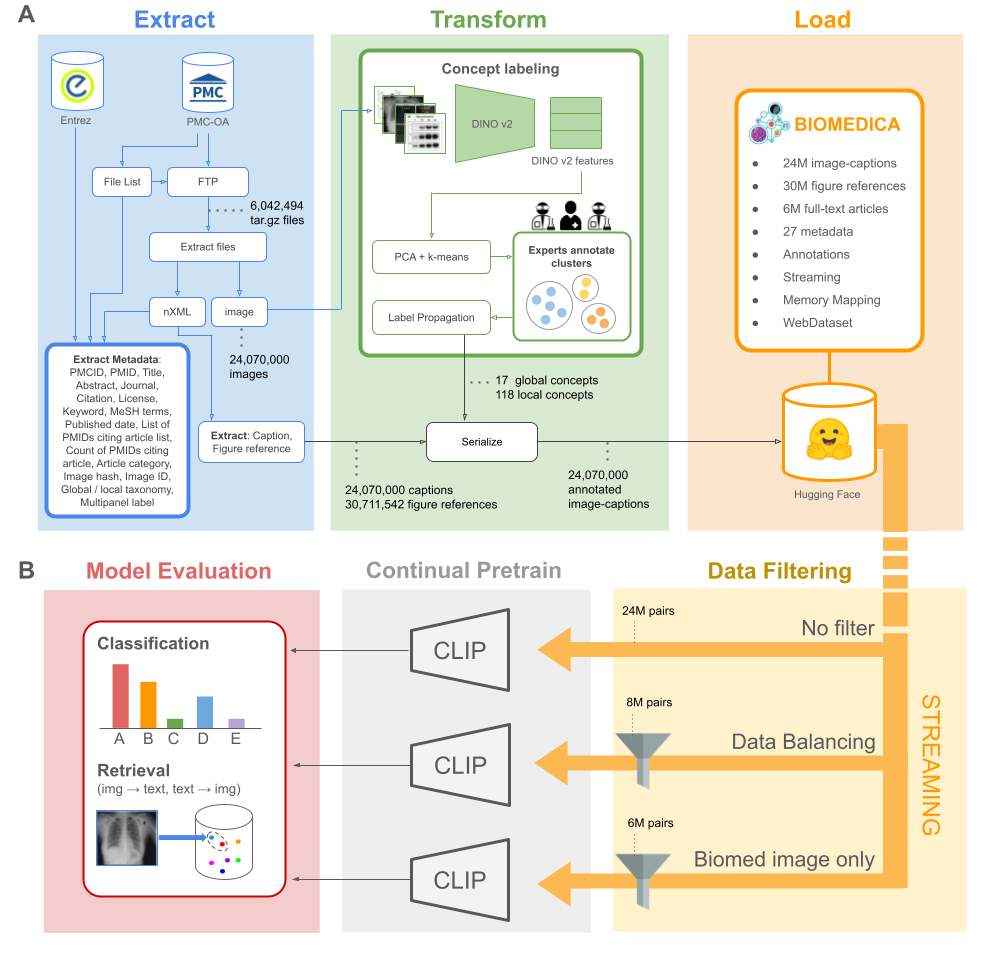

We examine the effects of continual pretraining on the full set of 27M image-caption pairs and compare these insights to (2) topic balancing, (3) dataset refining, and (4) robust fine-tuning. This topic exploration is non-exhaustive and it is specifically designed to utilize the supplementary annotations, metadata, and features that we have made available to the community.

For all experiments, we use a batch size of 1024 per GPU, distributed across 4 GPUs with a batch accumulation frequency of 2, yielding an effective batch size of 8192. As a result, each model processes the same number of data points at each training step. We use a learning rate of 1e-6 paired and 32-bit floating-point precision. All of our experiments are trained via streaming, eliminating the need for local storage of the 30 TB dataset.

1. Continual pretaining on full dataset (24M) In this experiment, we continually pretrain a CLIP (ViT-L-14) model on the complete dataset of 24,076,288 pairs. We train for 6 epochs. This experiment serves as a baseline to compare additional data mixture strategies.

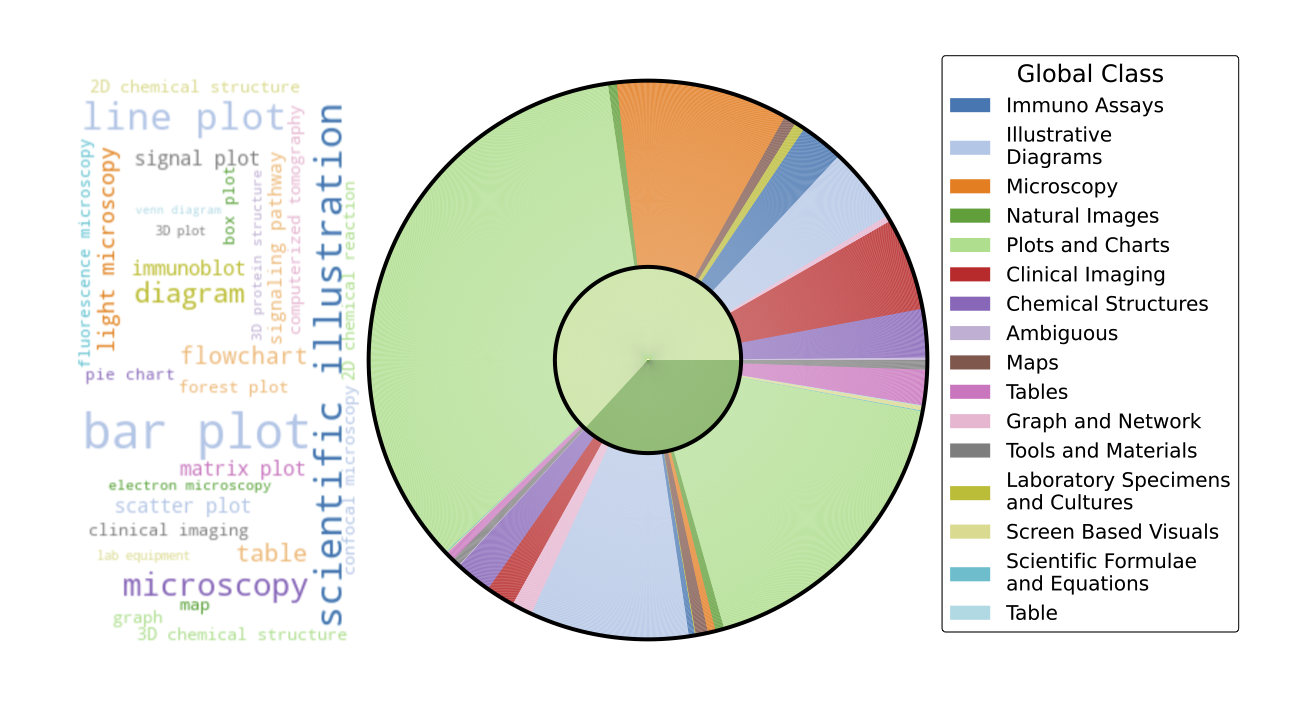

2. Concept-Balancing (8M) For this experiment, we continually pretrain a CLIP (ViT-L-14) model on 8,404,992 pairs, balancing all topics. To accomplish this over represented topics (e.g. plots) are dropped. By restricting the over-representation of any single category, this experiment targets potential biases introduced by data imbalance. We train for 16 epochs.

3. Concept-Filtering (6M) % Train Model on Only Biomedical Images In this experiment, we continually pretrain a CLIP (ViT-L-14) model using a filtered dataset of 6,602,752 image-caption pairs. This dataset includes only concepts within clinical and scientific imaging, immunoassays, illustrative diagrams, chemical structures, maps, tools and materials, and hand-drawn/screen-based visuals (excluding tables, figures, and scientific equations). We train the model for 21 epochs.

4. Robust Fine-tuning This experiment explores model merging by using a convex combination of the weights from a base model and its continually pretrained counterpart, as described in Wortsman et al. (2021), using the package introduced in Lozano et al. (2024). The goal is to determine whether combining the models' parameters leads to improved performance compared to individual models.

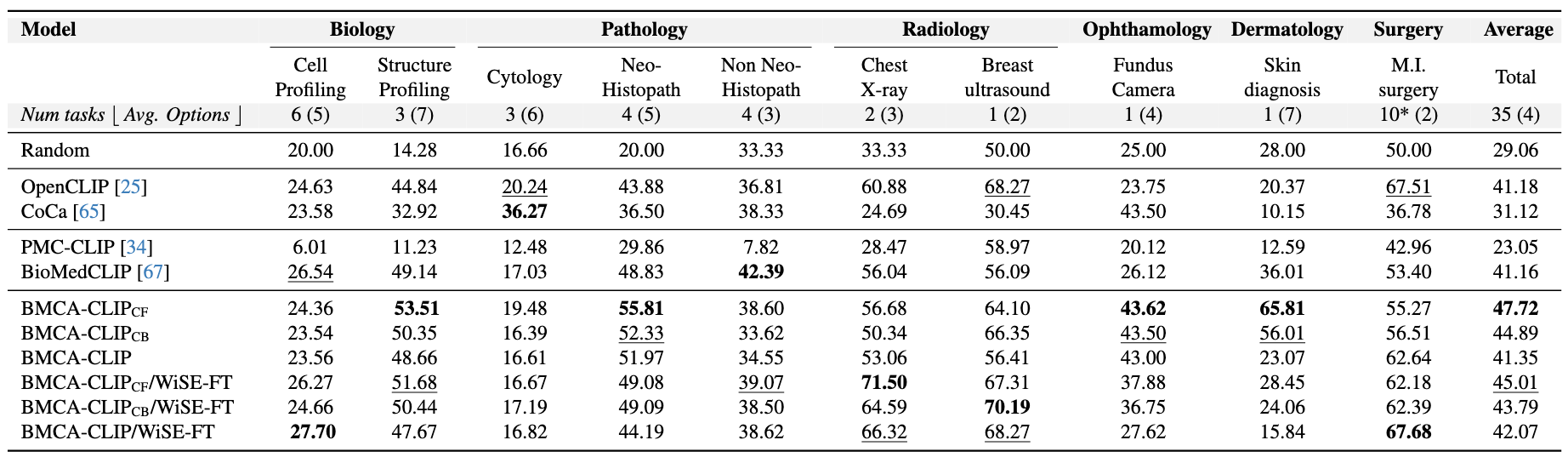

Benchmarking

The primary objective of large-scale continual pretraining on the BIOMEDICA dataset is to enhance the model's generalization capabilities across a wide array of downstream tasks within biomedicine. To evaluate the effectiveness of continual pretraining on BIOMEDICA, we repurposed 39 established biomedical classification tasks and leveraged a new retrieval dataset based on Flicker, for a total of 40 datasets.

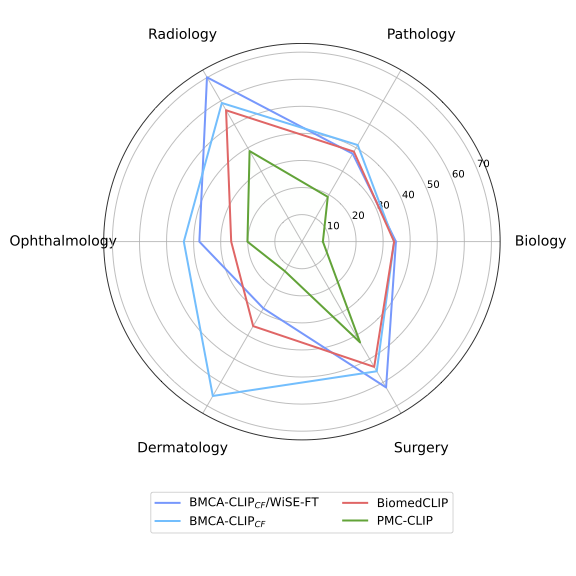

Image classification To construct a comprehensive classification benchmark, we take the union of evaluations from prior work (BioMedCLIP and PMC-CLIP) and supplement it with underrepresented domains. For each individual task, classes are converted into captions (see Supplements), providing two variations per class. This evaluation set spans multiple fields: pathology (11 tasks), radiology (3 tasks), ophthalmology (1 task), dermatology (1 task), surgery (10 tasks), biology (9 tasks) and general microscopy (4). The biology and pathology tasks are sourced from meta-datasets, including Micro-Bench Lozano et al. (2024); ophthalmology and dermatology tasks from MedMnist (Yang et al. (2023)); radiology tasks from RSNA (Shih et al. (2019)), and CheXpert (Irvin et al. (2019)); and surgery tasks from the Dresden surgical anatomy dataset (Carstens et al. (2023)). The image classification benchmark is subdivided into two splits, similar to Lozano et al. (2024). The first split, general bioimaging classification, includes tasks related to distinguishing abnormalities, making diagnoses, and identifying structures. This subset covers 35 tasks.

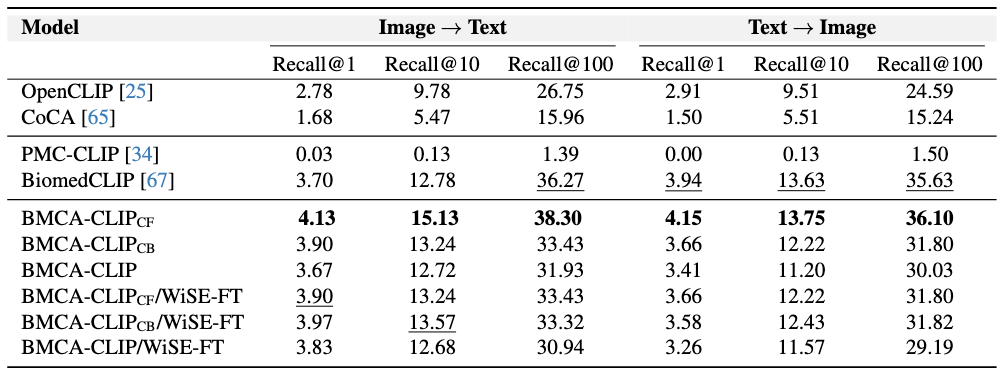

Retrieval task selection Since PMC-15M is not publicly available at the time of this manuscript, we cannot split BIOMEDICA dataset into the similar train and test sets as prior work while simultaneously ensuring a balanced number of concepts within each split. Therefore, we assess retrieval performance using a new collection of 7K high-quality, open-source biomedical image-caption pairs from Flickr. This benchmark spans concepts across pathology, radiology, biology, dermatology, and surgery.

Metrics Classification tasks are evaluated using average accuracy across two caption variations, while retrieval tasks are measured using retrieval at 1, 10, and 100. Despite variations in the number of classes and samples across tasks, summary statistics are reported as unweighted averages, ensuring each task is treated with equal importance.

Findings

Concept Filtering leads to better performance across zero-shot classification and retrieval tasks Intuitively, when compared to other continual pretraining strategies within BMCA-CLIP models, filtering the dataset (e.g., dropping over-represented topics like plots and tables) yields the best average performance across general biomedical imaging classification tasks with respect to concept balancing (better 80% of the time) and full-dataset pretraining (better 90% of the time). Additionally, concept filtering leads to superior performance compared to concept balancing or full-dataset pretraining in image-to-text and text-to-image retrieval. Indeed, within this training strategy, 48% of the data mixture corresponds to clinical imaging and microscopy.

Models Trained on the BIOMEDICA Dataset Lead to State-of-the-Art Zero-Shot Performance To address catastrophic forgetting Compared to prior work, models trained on the BIOMEDICA dataset yield better average performance in classification and retrieval tasks. BMCA-CLIP-CF outperforms PMC-CLIP in all tasks, achieving a +24.67% improvement in general biomedical imaging classification tasks, with a minimum gap of +5.13% in ultrasound (radiology) and a maximum gap of +53.22% in dermatology. Similarly, a +39.46% improvement is observed in microscopy composition tasks. Additionally, a recall@100 gap of +36.91% and +34.6% is observed in image-to-text and text-to-image retrieval, respectively. Similarly, BMCA-CLIP-CF outperforms BioMedCLIP in 8/10 general biomedical imaging classification subsets. yielding an average improvement of 6.56%. For individual tasks, BMCA-CLIP-CF achieves the highest differential performance w.r.t BioMedCLIP in dermatology (+29.8%), ophthalmology (+17.5%), breast ultrasound (+8.01%) and non-neo histopathology (+6.98%) and marginal better performance in microscopy composition identification and all retrial evaluations. It is noteworthy to highlight that BMCA-CLIP-CF achieves these results while using 10× less compute and 2.5× less data.

Robust Fine-tuning complements model performance in a subset of tasks Another advantage of our setup (continual pretraining) is its capability to improve individual task performance without further training. For example, in microscopy composition identification tasks, WiSE-FT improves BMCA-CLIP-CF by 8.16%, further increasing the performance gap with respect to BioMedCLIP. Similarly, WiSE-FT enhances BMCA-CLIP-CF's performance in 5/10 general biomedical imaging classification tasks (see Figure 4. Notably, BMCA-CLIP-CF increases the performance gap w.r.t BioMedCLIP in X-ray radiology (+15.46%), breast ultrasound (+11.22%), and surgery (+8.78%), complementing weakness in the original BMCA-CLIP-CF model. However, this gain in performance comes at the cost of lower performance in other subtasks, such as -7.56% in dermatology and marginally worse retrieval performance.

Conclusion

In this work, we present BIOMEDICA, a framework for converting PMC-OA into the largest deep-learning-ready dataset, comprising 24 million image-caption pairs with 27 metadata fields derived from scientific literature. We demonstrate the utility of the BIOMEDICA dataset by continually pretraining CLIP-style models, fully leveraging its expert-guided annotations, metadata, and streaming capabilities. Our results showcase the effectiveness of this resource, even in low-memory and GPU-constrained scenarios.

Our models achieve state-of-the-art zero-shot classification performance using prior open-source tools and models, while utilizing 10x less compute and 2.5x less data—underscoring the importance of large-scale annotated open datasets. The BIOMEDICA framework, dataset, models, and large-scale evaluation serve as a foundation for advancing vision-language research and applications in scientific and biomedical domains. We release all our contributions under a permissive license to facilitate broader use and further development.

BIOMEDICA

BIOMEDICA